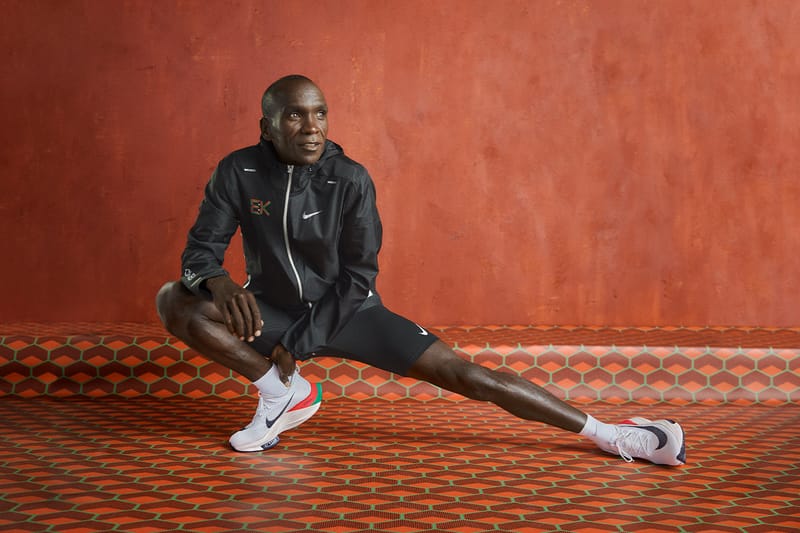

But this felt like a fairly unique opportunity. What was exciting about it was that I'm normally involved in trying to win races or winning Olympic medals. "When Jim asked me it was kind of 'take a deep breath' because this is going to be a lot of time and commitment. "I found out that I'd got cancer around March, which I wasn't expecting," he says. But Brailsford also had another issue to contend with far closer to home. Taking on such a massive project (between 300-400 people worked on it) during a hectic summer of professional cycling would have been a lot for anyone. "This sounds a bit geekish but I read quite a lot about how you can educate yourself quickly and learn fast."Ī month earlier Brailsford had been asked by his new boss, Ineos chief executive and Britain's richest person Jim Ratcliffe, whether he would take on a role as CEO of Kipchoge's attempt. By night he was studying into the small hours, learning as much as he could about marathon running. Kipchoge's sub two-hour marathon was anything but.įor Sir Dave Brailsford, the story began during the first week of May's Giro d'Italia.īy day Team Ineos' cycling boss was making sure the first Grand Tour since a switch from Sky's backing went smoothly. On the face of it, running is one of the purest and simplest sports on the planet. His design took two weeks for local workers to complete - "they thought I was nuts" - before it was undone and returned to normal 12 days later. Ketchell's solution was to dig up the roundabout and start again, turning the -2% camber into a +1% one.

Good for taking rainwater away from a tourist attraction, terrible for a marathon runner trying to make an about turn while travelling at 13mph. The presence of a historic building in its centre meant that the road had been designed with a -2% camber. He is a man well schooled in sport's one percent advantages - the so-called marginal gains. Why? As a data scientist Ketchell has helped Team Ineos (formerly Team Sky) win three Tours de France. For the next four hours until sunrise, he kept a one-man watch over this hump in the road - a pivotal piece in the complicated jigsaw of Kipchoge's 1:59 Challenge. Ketchell was desperate to check nobody was trespassing on a small roundabout that had been his second home for the past two weeks.

He was so unsettled that he jumped out of bed and hotfooted it 3km across Vienna. But 3,500 miles away in Austria, American scientist Robby Ketchell was woken by a nightmare at 3am.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)